The Holocene Epoch of this Quaternary Period appears to be coming to an end. Our arrogance views this as the beginning of the “Age of Humankind”. Scientists tentatively call this new epoch, the Anthropocene, named after the Greek word for “human”. The first clear sign of our dominion over all things was climate change. The second was a mass extinction event happening 1,000 times faster than ever before – the Sixth Extinction. The Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic is the latest sign. A man-made global crisis that nature cannot help us with. The human body has never before encountered this virus, nor should it ever have had to. We are at the “Dawn of the Anthropocene”, and “dawn” can signify the beginning, or the end.

There is a misconception that the Anthropocene is somehow an accomplishment, or an expression of power and technological advancement. It is none of these things. Epochs are described according to fossil records contained in layered strata of rock and sediment. Geologists envision a prominent fossil record characterised by visible accumulations of extinct wildlife below livestock, concrete, garbage and humans, all set in a narrow band of rock layered across the Earth. The Anthropocene will be our eternal legacy etched into this rocky planet. Our final obituary, and a warning to those that come after us.

This Coronavirus pandemic has us slipping into the dangerous geopolitics of isolation, nationalism, and recession. We are to blame for the climate disasters, mass extinction, human migration, water and air pollution, war and civil unrest, inequality, global poverty, and diseases, that threaten our modern civilisation. Ebola, Zika, SARS, MERS, COVID-19 and others still unknown will emerge from wild species in remote areas to terrify us. Disease epidemics have played an important role in ending civilisations throughout history. In the Americas, smallpox wiped out the Incas and many Native Americans tribes. Wave after wave of small pox broke these civilisations down into a state of civil unrest, starvation, and chaos. These epidemics were not natural back then, and are certainly not natural now.

Today, is the second day of a 21-day government-enforced lockdown to curb the spread of the coronavirus here in South Africa. No one is allowed to leave their properties for three weeks. We are not testing enough and our healthcare system will not cope with thousands of people needing ventilators. We are vulnerable. If this virus can get to Prince Charles and Tom Hanks, it can get to anyone… Quarantine and panic-shopping made us feel that we were no longer in control, which was terrifying. Self-isolation and social distancing will become our new normal. There are still many stories of sharing and self sacrifice, but the worst of this pandemic is yet to come, and come, and come again… We are going to be tested by this pandemic.

It is ironic that the illegal wildlife trade may be the end of us, and not the diminutive pangolin, or this sitatunga. In modern times, consuming “bushmeat” has reliably unleashes terrifying new disease epidemics into our towns and cities. Again, this is definitely our fault. We simply left nowhere for these malicious pathogens to hide as we continue to drive wild species to extinction with fire and firearm in remote wildernesses across the globe. It may be culturally-acceptable to eat a bat right now in Vietnam, but this is not justification enough for this activity. Real leadership is about bold change that is accepted by the people. Right now, we need to stop eating and wearing exotic wildlife, and start protecting their natural habitats as our own. Protecting wildlife and our planet’s last wild places must be the “Great Work” of the living generations today.

Earth’s last wild places are those places that, for whatever reason, were never settled, developed, or converted. Places protected by their remote inaccessibility. Places we hardly ever go. These last untouched wildernesses at the ends of the Earth are our last living glimpses into prehistory. Landscapes, and seascapes, that remember a time before modern man. An enlivening vision of the wildernesses we came from and the formative power that created us. Now, with 7,5 billion of us on the planet, we are entering these last Edens, effectively breaking into the central banks of the natural world. The sources of life on Earth. Are we setting upon destroying them? I am not sure. I do know that it is our cities that are eating and wearing our last wildlife, not the indigenous people living in our planet’s last wild places.

Our modern concept of “wilderness” arose from the wild forests, mountains and prairies of North America in the writings of the great wilderness thinkers of the 19th and 20th centuries: John Muir, Henry David Thoreau, Aldo Leopold, and Edward Abbey. They put forward the notion that having access to pristine wilderness was somehow keystone to being human. To them it was not only the bear, elk and mountain lion that was at risk. They seeded the idea that our shared human experience in the wilderness is foundational to our collective sanity, and our very humanity.

Now, I am not a particularly religious or spiritual person, but, I believe that, in the wild, I have experienced the birthplace of religion. Standing in front of an elephant far away from anywhere is the closest I will ever get to God. Moses, Buddha, Muhammad, Jesus, the Hindu teachers, prophets and mystics all went into the wilderness, into the desert, or up into the mountain to sit quietly and listen for those secrets that were to guide their societies for millennia. I go “Into the Okavango”on my mokoro. You must join me one day.

10,000 years ago, our entire world was wilderness. Today, wilderness is all that remains of that world. 10,000 years ago, we were as we are today, a modern, dreaming intelligence unlike anything seen before, living in the wildernesses that taught us to speak; to seek technologies like fire and stone, bow and arrow, medicine and poison; to domesticate plant and animal; and to depend on each other and all living things around us. We are these last wildernesses every one of us.

To me, the concept of “wilderness” is rooted in the human experience and the basic principles of freedom and security. If your local community has retained the traditional knowledge and land rights necessary to visit and live traditionally in their wilderness relying only on nature, you are still free. You have a place where you can go where you know you can subsist off the land, depending on the abundance of life still resident there. A place where you depend only on the people with you. That is freedom. Life is about finding a balance between power and freedom. If you could leave the city to survive sustainably in the wild without malls, doctors, supply chains, or any services, you would be a lot less afraid of the next catastrophe to befall us. That is security.

Whether COVID-20 or a meteor strike, our fear of these cataclysms is born out of not being in control. We depend on our governments, not nature, to save us. Our situation is so dire that we need saving. Living traditionally in the wild was very hard, but, for millennia it gave us the two things we needed most to live free and happy. Today, we live in cities with our digital distractions, but are still drawn to our planet’s wild landscapes and seascapes for our holidays. We are drawn to them because these places make us feel like we are part of something. They make us feel alive, enlivened. We need wild nature to reconnect with who we really are.

Personal experience living and working in the wilderness has taught me that the most connected to this planet you will ever feel is when learning how to survive in the wild. In the Okavango Delta, Botswana, where I have worked for almost 20 years, if you can pole a mokoro, catch fish, harvest water lily rhizomes, papyrus, mopane worms, and wild fruits, and know how to live with dangerous animals, like hippo, lion and elephant, you will survive sustainably for as long as you need to. Everything you need from toothpaste to medicine to chewing gum can be found in this wilderness. The Wayeyi people call the delta, the “Mother Okavango”. The great provider of everything they need to survive, and be happy. Connected the Wayeyi are alive. Disconnected alcoholism and despair capture them. Magic and mysticism thrive in the wild where the campfire is your therapist, ancient baobab trees stand like cathedrals, and a million bell frogs become the sound of creation. Paradise on Earth.

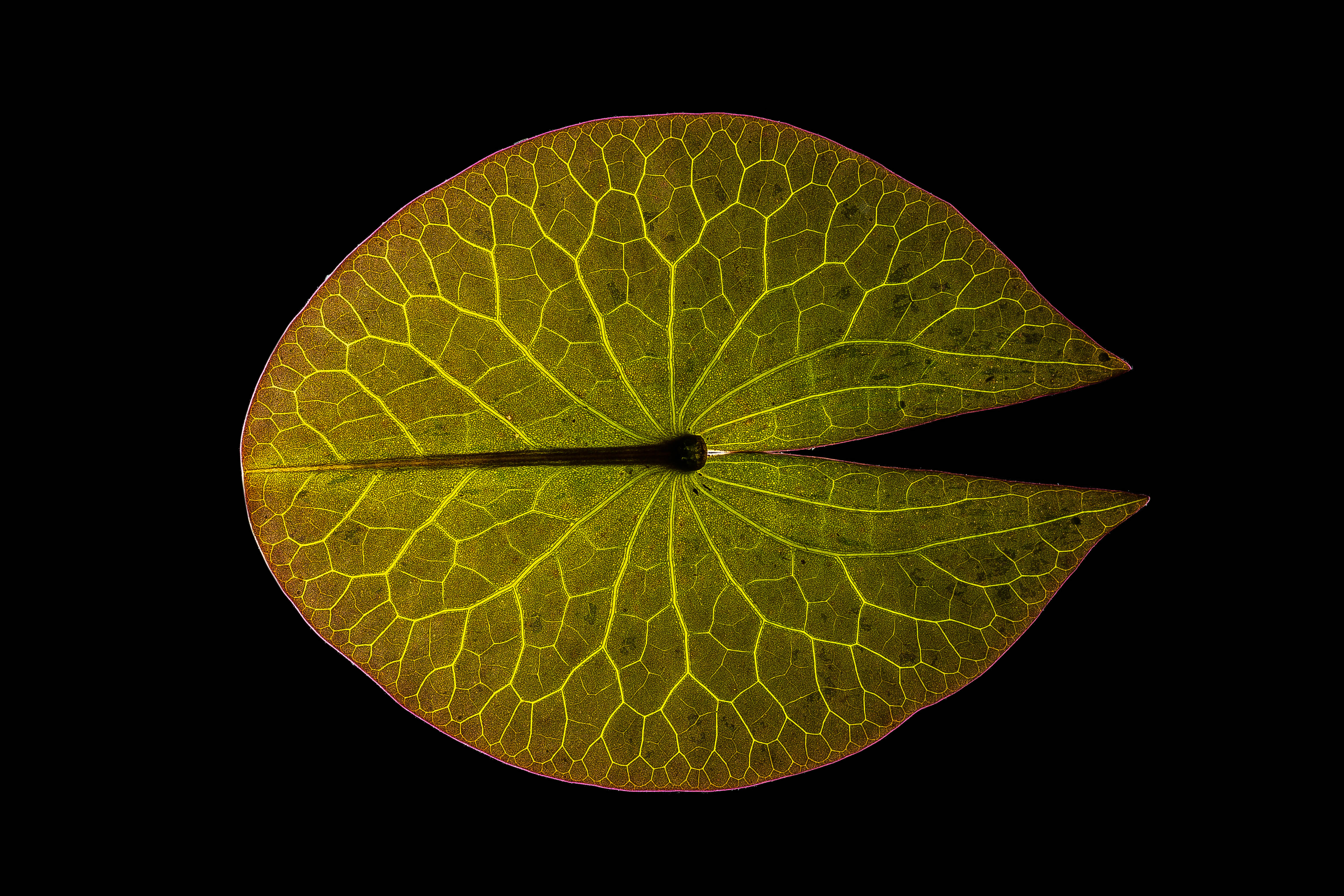

In the words of John Muir: “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.” We, all 7,5 billion of us, must never forget that we are a biological species forever bound to this particular biological world. Like the waves connected to the ocean, we cannot exist apart from it. A constant flow of atoms and energy between individuals and species around the world in a day and out into the cosmos. A “life tide” that washes through us every day and connects us to all living things in time and space. An average person has an estimated 30 trillion human cells and an astonishing 39 trillion bacterial cells. Some people have more bacteria, some people have less, sometimes by several factors. In essence, we are upright-standing bipedal ecosystems dependant on the interactions of millions of benign bacterial species that we do not know, and periodically try to kill. Our bodies are a microcosm for our world, an unbreakable partnership more complicated than we can begin to imagine. We are these last wildernesses every one of us.

You must never forget. You are a mammal like a horse or a dolphin, just 8 million years separate from a chimpanzee, who shares 99% of your DNA coding. In fact, in us we carry the genetic coding of all living creatures that preceded us. Astonishingly, humans share about 60% of our DNA with bananas. We are nothing if we are not wild, sharing the same fate as all the other species that evolved alongside us, in partnership. We are together. Humans are not the pinnacle of evolutionary achievement as most people think. All living species alive now are at the top of our evolutionary lineages, an unbroken chain of births and deaths from the dawn of time. This is what makes all species and individuals equal. We are all survivors of the last cataclysm to trigger a mass extinction. We are all together in this journey and, in the end, will all share the same fate.

All over the world, miners, loggers, dam engineers, entrepreneurs, tourism developers, armed militias, and conservationists are effectively breaking into the central banks of the natural world. Our globalised, modern world is reaching into these last wildernesses to unknowingly exploit them for the first time. Most of the devastation we have wrought upon the Earth was completely unintentional, but this seems to be deliberate. Who knew CFCs would eat a hole in the ozone layer, that excessive CO2 would warm the planet, that fur coats could cause extinctions, or that beautiful teak floorboards for your home would deplete African forests? Not many consumers know the consequences of their purchases because these consequences are often hidden from us. We must connect consumption with material consequences. We are the living generations that unknowingly, and sometimes deliberately, did the most damage, but we are also the living generations that predicted the future consequences, developed a plan, and are now mobilising to fix what our grandparents, parents and ourselves have done.

Now in the 21st century, over 80% of planet’s land mass is experiencing measurable human impacts. For the first time, our entire world is bending under the weight of one species – our cities, mines, dams, farms, ports and suburban developments. We are unprecedented. According to the world’s top scientists and experts, protecting at least 30% of the world’s landscapes and seascapes by 2030 would provide us with a strong foundation from which to rebuild towards a sustainable future. By 2030, we need to position to shift from protection and stewardship to the restoration of failing ecosystems, degraded landscapes, and depleted wildlife populations, if we are to survive this looming apocalypse. By 2050, we either have a future on this planet or we don’t. If we continue to burn and bulldoze our planet’s last wild places more and more horrors, like COVID-19 and Ebola, will emerge to correct the imbalance we have created.

Astonishingly, air quality in northern Italy and Spain has improved drastically because of the coronavirus lockdowns. Starving “monkey gangs” of thousands of crab-eating macaques are marauding through the ancient city of Lopburi in Thailand. In Italy, Venice’s canals have gone clear and filled with fish. Wild baboons are entering the streets of Cape Town due to the government lockdown. We need to part of the solution, not the problem itself. It cannot happen that every time we are removed from a place, it becomes less polluted and recovers to support a diversity of wild species. Just as important as protecting our planet’s last wild places where we do not live or not many of us live, we need to find ways of welcoming wildlife and biodiversity back into our cities. We must stop eating wild species and start caring for them as our equals.

This novel coronavirus is scary because we have to rely on modern technology and our healthcare infrastructure, and not nature and our collective immune systems, to protect ourselves from it. Nature doesn’t have remedies for unnatural events like this. We arrogantly thought we could do it, but we can’t, and now we are dying and hiding afraid in our homes. Most people do not have the land, or opportunity, to grow their own food, and freshwater is no longer freely available in a river or stream nearby. There are no fish to eat in the lake, no animals to hunt in the city, and no edible fruits to harvest from the trees. We have become almost completely dependent on the governments we vote for, and the corporations that feed and cloth us. We need to find a balance that integrates nature in as many aspects of our modern lives as possible. We must learn how to consume less by relying on nature more.

Without presence, empathy and radical change our iteration of complex life on Earth, the story of us over the last two or three million years, will come to an end. Now, in the 21st century, we are the last-remaining human species, hominid, of many. The last hominid standing. Each human species was perfectly evolved for their time and place whether it be living on an island, a continent, a forest, or an ice cap. Alongside, and perhaps in conflict with, our fellow hominids we lived connected to all living things around us, or we would not have survived. Disconnected we too will be forgotten.

Through hobbits, goblins, trolls, sasquatches, minions and munchkins, fiction and folklore, we re-imagine an ancient world in which we were not alone. What happened? We will never know, but as recently as 25,000 to 50,000 years ago, there were at least five different human species sharing this unique blue-green planet with us. This included us, of course, the Denisovans and Neanderthals, the recently discovered Homo luzonensis that lived on the island of Luzon in the Philippines, and the famous “Hobbit”, Homo floresiensis, from the Indonesian island of Flores. Even the diminutive and seemingly ancient Homo naledi, discovered a few years ago, was “almost human” and evidently walking around with us as recently as a quarter million years ago.

We will not be the first human species to go extinct, but we will almost certainly be the last. Having several living lineages of extinct Homo species alive today, big and small, would have been a much better insurance policy than becoming multi-planetary as suggested by Elon Musk. We are now alone, and yes, we may need a viable lifeboat. Musk wants millions of people to migrate to Mars starting in just 10 years (or sooner). A mass emigration of people from around the world to a planet completely unsuitable for human habitation or sustainable civilisation. Jeff Bezos envisions trillions of human beings spread across the galaxy in a thousand years. Are they trying to save humanity from something, or simply engineer a future for their children that excites and motivates them? What do they know that we do not?

Must we become multi-planetary to survive as Homo sapiens? Or did these visionaries, Musk and Bezos, just watch too much Star Trek or Star Wars as teenagers? I mean, I saw Al Gore’s “Inconvenient Truth” in 2006, while at UC Berkeley, and was shocked to say the least, but I certainly didn’t decide right then to start making plans to build a starship to take us all to Mars. My thoughts and discussions were all about saving our planet, and humanity, from what, at least back then, was perceived to be an avoidable doom. It is very scary that we are already looking for a lifeboat and somewhere else to live other than Earth.

Perhaps this mass extinction, our “Anthropocene Extinction”, is already a mathematical inevitability? Perhaps climate disasters and this coronavirus pandemic are signs of the beginning of the end? Perhaps the situation is worse than we have been made to believe? Maybe we are worried about the wrong things? In his final documentary, Stephen Hawking warned us that, if human beings do not leave Earth within 600 years, we will go extinct. His original warning was for us to leave by the turn of this century. If we go to Mars, we will have to depend exclusively on technology to survive; to breath, to eat, to drink, just to be there. Perhaps we should learn how to live on Mars to prepare for Earth that cannot support life as we know it?

An estimated 30 million square kilometres of wilderness remains, over 50% of which is unprotected state, communal, or private land. This is an opportunity, a chance for us all. We need to act with great urgency to secure and protect our planet’s remaining unprotected or protected and poorly managed intact wild ecosystems. Over the next decade, we need to make an unprecedented direct investment into the preservation of our planet’s last wild places for people, wildlife, and ecosystems. Inspired to protect this wild beauty and grandeur, the mission statements of the National Geographic Society’s Last Wild Places program, the Wyss Foundation’s Campaign for Nature, and EO Wilson’s Half-Earth Foundation, as examples, all focus on protecting 30% of our planet’s last wild landscapes and seascapes by 2030, 50% by 2050. All three are new programs established over the last few years. Billions of dollars are being secure for investment in the preservation of our planet’s last wild places for the benefit of people, wildlife and biodiversity. We are mobilising a big effort to protect the wildest parts of the planet by 2030. This is the most important decade in history for the global conservation movement. If we do not fix this, the gradual, but accelerating, degradation of the natural world will continue making our long-term tenure on this planet unlikely. The last fortresses for global biodiversity are being torn down, releasing pathogens like COVID-19. We are about to burn the book of life.

The “Great Work” of the living generations today must be to secure 50% of our planet’s surface, land and sea, for conservation, sustainable use, and nature by 2050. Some of the solutions to achieving this are clear, but many still need to be discovered. We need to re-affirm our deep connection to nature and our origin in the wild. We need to find balance before it is too late. Together, we can imagine a future for 10 billion people living better and longer surrounded by nature on this shining blue-and-green planet, the third rock from the sun. We need to protect our last wild places and find ways of welcoming wildlife back into our cities, and onto our farms. Reconnected to nature, we will survive in partnership with all of the species we evolved alongside. Again, we are a biological species forever bound to this particular biological world, so we had better take good care of it, now that we are in charge…