Deconstruct to Reconstruct: How Providence Health System Built an Internal Talent Marketplace

The Business Challenge

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the family of organizations that make up the Providence healthcare system faced a severe shortage of healthcare workers. Long before the pandemic hit, myriad forces had been at work that portended a crisis-level talent shortage in healthcare. Specifically, enrollment of students in nursing schools had been nowhere near the rate needed to meet current and future needs. Compounding this, nursing schools across the country were struggling to expand capacity to meet the rising demand for care in view of the national move toward healthcare reforms.

In addition, nurses had been leaving the workforce in significant numbers in the U.S.; doubling in the past decade from 40,000 in 2010 to an estimated 80,000 in 2020, due in part to a significant segment of the nursing workforce being close to or nearing retirement age.

Then came COVID-19, which only served to exacerbate the existing strain on the healthcare talent landscape.

The Solution

![]() Founded in 1859, the Providence health system operates 51

hospitals, more than 1,000 clinics, and a comprehensive range of health and

educational services across Alaska, California, Montana, New Mexico, Oregon,

Texas, and Washington. Providence is committed to advocating for vulnerable

populations and its leaders are passionate about driving needed reforms in

healthcare.

Founded in 1859, the Providence health system operates 51

hospitals, more than 1,000 clinics, and a comprehensive range of health and

educational services across Alaska, California, Montana, New Mexico, Oregon,

Texas, and Washington. Providence is committed to advocating for vulnerable

populations and its leaders are passionate about driving needed reforms in

healthcare.

While Providence leadership at the local and system levels had been at the beginning stages of revamping how they build, grow, and retain talent prior to the pandemic’s onset, this effort needed to accelerate to ensure they could successfully meet the needs of their patients and communities.

“We've been planning for the future of work, workforce, and workspaces for a long time. And despite all the catastrophic impacts COVID-19 has brought with it, one silver lining—at least in healthcare—is that it has probably accelerated our progress in a lot of these areas by at least five to 10 years.” says Greg Till, Chief People Officer at Providence.

The Institute for Corporate Productivity’s (i4cp) recently published 2021 Priorities and Predictions report confirms that high-performance organizations are 2x more likely to prioritize talent mobility than low performance organizations. Further, the research found that the ability to move talent (as well as innovative ideas and critical knowledge) across an organization’s ecosystem can help build, develop, and sustain bench strength in critical roles, establish and strengthen key interdependencies, and break down destructive silos.

Building an Internal Talent Marketplace

With a view of this landscape and the added burden of COVID-19, Providence was able to accelerate the development and use of an internal talent marketplace. i4cp’s research indicates that high-performance organizations view talent as enterprise-wide team members rather than belonging to a leader, team, or business unit. In addition, high performance organizations make intentional internal mobility a priority.

Till explains how Providence was able to leverage these practices: “We partnered with our clinical, functional, and operational leaders to define the critical skills and capabilities that would help our facilities deal with the pandemic effectively. Then, we did our best to assess which of our 120,000 caregivers had those skills, regardless of where they served.”

The approach Providence took was to fully deconstruct and then reconstruct all components of their talent management system with a focus on flexibility and agility to ensure local facilities’ urgent needs were met. An internal talent agency mindset was adopted to handle dynamic shifts in demand more quickly and effectively.

To that end, an internal team developed and sent a survey to each Providence caregiver, asking them to provide information regarding their certifications and current qualifications. The collected data, which was binary (one either has the skill or not) was then manually collated into a low-tech database.

To utilize this data, an internal talent marketplace committee was established comprised of 75 people who in total represented each health care facility. This committee, whose goal was to assess needs across the system and ensure each had caregivers with the needed skills available to meet dynamic demand, initially met several times per week to review the current status of each site. A smaller team then took this input and developed a “red/yellow/green” assessment. When there were sites with a forecasted red or yellow (immediate or near immediate need of certain skills), those with the skills needed were redeployed to those sites until the urgency subsided.

Says Till, “From the very start, everyone had the same goals—provide exceptional compassionate care where needed in our communities and ensure all of our caregivers had meaningful work, even those in facilities that saw a significant decrease in volume at the beginning of the pandemic.”

Collaborative relationships with organized labor and the temporary relaxation of government restrictions supported this approach, allowing caregivers to be temporarily redeployed to the areas of highest need.

Building on these manual processes, Providence applied advanced analytics, using historical patient volume, COVID-positive rates, retention statistics, and other data to effectively predict staffing needs several months in advance, which not only ensured each site had the support needed, but also reduced vacancy, agency expense, and additional overtime for caregivers who were already working incredibly hard.

Another key goal of developing Providence’s internal talent marketplace was to ensure all caregivers had and continue to have the opportunity to work in roles they feel “called” to do. Says Till, “Ensuring caregivers are able to do the work they love is one of the primary contributors to job satisfaction and personal fulfillment. People find meaning in work they are call and trained to do. Every minute a nurse, pharmacy tech, or finance analyst spends doing work they feel is ’below their license,’ is wasted—it contributes to lower engagement, less connection to the meaning in work, and creates excess cost.”

An additional example Till shared was that prior to the development of the internal talent marketplace, it took a highly skilled nursing manager several hours to create a bi-weekly schedule. Using the input of the predictive models referenced earlier, several Providence facilities are now piloting a ‘schedule optimizer’ which automates the task of taking all the information about patient demand and workforce supply, caregiver preferences, and other criteria to create the schedule. What used to take several hours now takes less than a minute which means the nursing managers can turn their attention to the work they are most passionate about.

More HR Innovation

Resistance to hiring before a need presents itself is not uncommon—but using the data described above, Providence has been able to demonstrate the benefits of doing so. Because their facilities now have data that allows them to predict demand in advance, they can post roles ahead of the need, ensuring they are scrambling to meet hiring needs much less often.

By hiring ahead of the need, Providence has been able to show that this approach ultimately is more cost effective as it reduces overtime, external agency utilization, and the need for patient deferrals—and at the same time increases caregiver engagement.

Till is also focused on turning HR into a revenue generator rather than a cost center as is historically the case. While they are still in the early days of this effort, Providence is in conversations with a number of large organizations that are looking to enter the healthcare space with the goal of creating a saleable and monetized product that other companies would be able to use to design and develop their own internal talent marketplace.

Final Notes

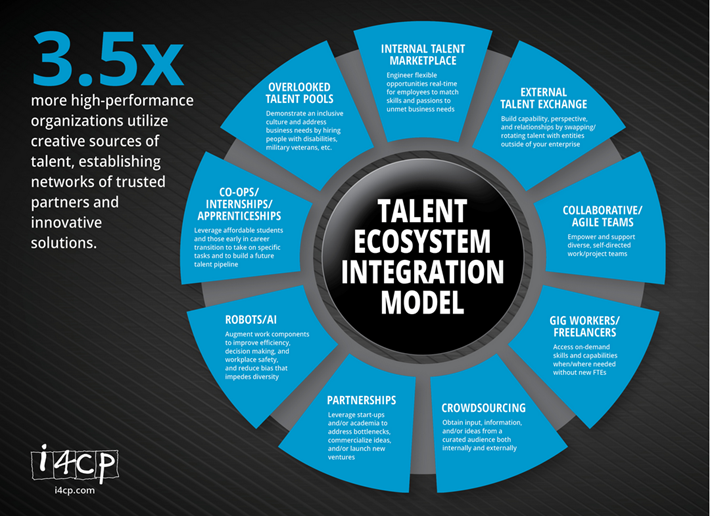

Till noted that while leaning on i4cp’s Talent Ecosystem Integration Model™ to drive the development of an internal talent marketplace has been very beneficial, healthcare is an industry in which the collection of skills and certifications are relatively objective and therefore more easily assessed.

Skills and certification collection can be much more complex where responses aren’t as clear and/or might require a qualitative element (i.e., leadership effectiveness). However, organizations regardless of type, size, geography, growth stage or focus can benefit from utilizing the i4cp model to ensure all areas of the talent landscape are being reviewed, the right questions are being asked, and no element is overlooked.

It is also worth consideration that talent leaders not wait for complex systems or advanced technology to get started on building an internal talent marketplace. It may be enough to have an internally built and administered survey and access to basic spreadsheet software (i.e., Excel) to get started while simultaneously investigating technology solutions that will scale.

The pandemic and the other disruptive events over the past year have pushed many organizations to make significant changes that must be executed at lightening-speed and to adopt new ways of thinking about talent—perhaps before they were ready. Now that we are here, it may be time to leverage the burning platform that has presented itself and take some real steps toward new ways of managing talent.

Development and use of an internal talent marketplace is a next practice in innovating solutions to business challenges; i4cp defines next practices as strategies that show correlation to better market performance but that are not yet widely adopted. Typically, next practices are applied more often by high-performance organizations.

An internal talent marketplace is one of six

key components of i4cp’s

Talent Ecosystem Integration Model ™.

Click the link to view other case studies that bring this model to life.

Kari Naimon is a Senior Research Analyst at i4cp.