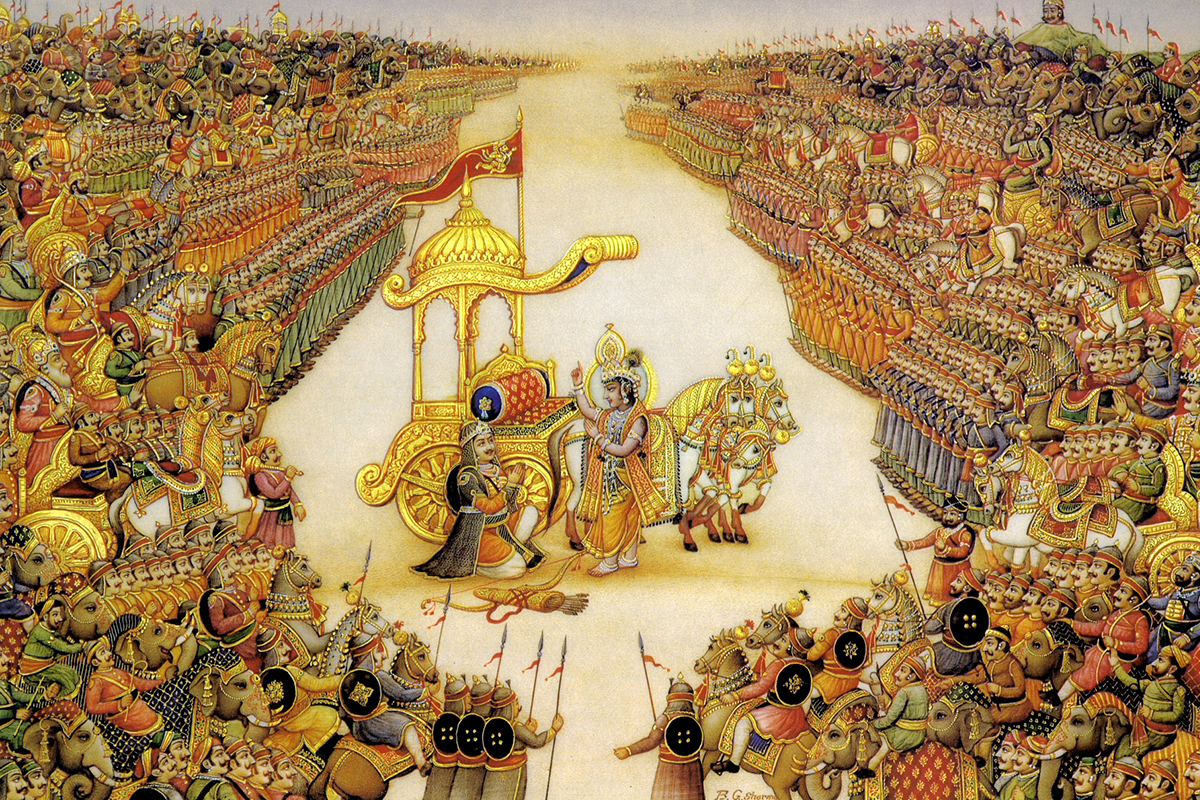

The interview below has been lightly edited for clarity, and includes Vedic artwork by B.G. Sharma and unknown artists.

The Bhagavad Gita is an intimate dialogue between Krishna and his disciple and friend Arjuna, and it is a 700-line section of a much longer Sanskrit epic, known as the Mahabharata.

Throughout the Bhagavad Gita and many of the other books that constitute the Vedas, Krishna is referred to as the Supreme, the source of existence as we know it, and the eighth avatar of Vishnu.

Arjuna is a Kshatriya — a human member of one of the four varna or social orders that defined Vedic society and a social order associated with warriorhood.

For all intents and purposes, Arjuna was a warrior prince and a yogi.

Throughout the Bhagavad Gita, Krishna serves as Arjuna’s charioteer at the Battle of Kurukshetra, a battle between Arjuna and his kin, known as the Pandavas, and their opposition, prince Duryodhana and his kin, who were known as the Kauravas.

The Battle of Kurukshetra came about because the Kauravas had dishonored the Pandavas in various ways. It was part of Arjuna’s many duties to wage war against them in defense.

The battle was a perplexing and seemingly unwinnable situation from Arjuna’s perspective, as his forces were outnumbered, and years before, he saw the Kauravas as his kin.

In fact, many of his closest friends and mentors and some of his family members were waging war against him, and he was tasked with killing them.

Despite his years of training as a Kshatriya, despite being far more competent than some of the greatest warriors at the time, the Bhagavad Gita depicts Arjuna’s anxieties, his lack of faith in his training, his lack of faith in his duties, his lack of faith in Krishna, and his need for material certainty, even though he knew that Krishna was omniscient, omnipresent, and omnipotent, and even though he understood that Krishna knew what the specific outcomes of the battle would be.

Despite possessing the tools to navigate a variety of challenges, many of us find ourselves in perplexing and seemingly unwinnable situations like the one that Arjuna experienced during the Battle of Kurukshetra, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, whether it be in business or in other aspects of our lives.

As such, all leaders can benefit from reading the Bhagavad Gita and other Vedic texts.

Whether it is interpreted literally, or from the perspective of one that wants to understand human history, or from the perspective of one that is intrigued by philosophy, or from the perspective of one that is interested in human nature and psychology, or from the perspective of one that is seeking spiritual knowledge and the fundamental truths of existence, the Bhagavad Gita is worth the read, it is an incredible story.

The Gita is one of the most fascinating and influential books in existence and one of my favorite books, if not my favorite book.

I first began reading and studying the Bhagavad Gita and other parts of the Vedas four years ago, following an existential crisis in 2014 that inspired me to learn more about myself, my sources of suffering, childhood trauma, how I had been psychologically conditioned, personal development, and spirituality.

In 2017, through the platform Meetup and my desire to connect to like-minded individuals, I joined a spiritual group called Bhakti Lounge, wherein I started learning about and practicing kirtan — a form of meditation and music that is defined by chanting Vedic mantras.

Bhakti Lounge also introduced me to bhakti yoga, which is a form of yoga that is defined by a loving devotion towards a personal deity.

Through Bhakti Lounge, I received my first copy of the Bhagavad Gita, specifically “Bhagavad-Gita as It is” by A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada.

And so, I began slowly reading it diligently, and I have been integrating wisdom from the Gita and other Vedic texts since 2017.

By 2017, I had been practicing hatha yoga and engaging in different forms of meditation every day for three years, and yet I did not know what yoga truly was or why hatha yoga was first developed, or where a variety of meditation practices stemmed from until I began reading the Gita.

I soon learned that different forms of yoga prepared the mind and body for one’s duties, life’s inevitable challenges, and ultimately for death.

In fact, the Toronto-based Vedic monk Bhaktimarga Swami, who is known as “The Walking Monk,” once told me that yoga teaches one how to “die before dying.”

Despite the often impressive optics associated with hatha yoga, I learned that it is not the most challenging or useful form of yoga, in many cases, especially when one’s hatha yoga practice is devoid of the philosophies of the Vedas.

For example, karma yoga is the yoga of engaging in one’s duty or duties without attachment to one’s personal needs or discomforts, regardless of one’s notions of the past and future, regardless of pain or pleasure, and regardless of the inevitability of physical death.

From my perspective, practicing karma yoga is far more challenging than a headstand or any other asana from hatha yoga.

Due to its profundity and complexity, and because I often read multiple books simultaneously to connect the dots between them, it took me about a year to read the Gita the first time.

Reading the Gita also taught me that becoming a yogi is a tall order that may be impossible for most people to experience, especially those employed full-time or part-time in the western world.

In fact, although I practice hatha yoga and other forms of yoga every day, I do not consider myself a yogi, nor do I consider most hatha yoga teachers and practitioners yogis.

At best, most of the hatha yoga practitioners that I have met are proficient at physical exercise and know little to nothing about the purposes of hatha yoga.

Months after my introduction to Bhakti Lounge, I began managing the organization’s social media and engaging in content marketing consulting for the organization.

Eventually, I began learning more about the Vedas, the Bhagavad Gita, and different forms of yoga through the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON) in Toronto, which is sometimes referred to as the Hare Krishna movement, and a group called Kirtan Toronto, as they were both associated with Bhakti Lounge.

I am grateful to everyone that I have met through Bhakti Lounge, Kirtan Toronto, and the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON), as they have all had a profoundly positive impact on my life, especially during the periods of incredible hardship that I have experienced since 2017, like the deaths of one of my aunts and one of my great aunts within the same year, and the many challenges that come with modern life and entrepreneurship.

My friend Raseshvara Madhava is the co-founder of Kirtan Toronto.

I consider him one of my spiritual teachers, and he recently introduced me to one of his teachers, Rasanath Das.

Rasanath Das, who is of Indian descent like Raseshvara Madhava, and who lives with his family in Brooklyn, New York, walked away from a job in investment banking to become a Vedic monk, after simultaneously engaging in both paths for a time.

Today, Rasanath Das is no longer a monk. Instead, he is the co-founder of Upbuild, alongside his business partner Hari Prasada.

As described through the Upbuild website, “Rasanath and Hari Prasada started Upbuild in a monastery in the East Village of Manhattan in 2008 as a product of their own search for self-realization.

They were intimately studying the Bhagavad Gita and other sacred texts of the bhakti tradition in order to apply them to their own lives.

It became very clear to them that the goal of life is to become one’s real self, and the greatest, ever-present obstacle to that goal is the ego.

It also became clear that anyone attempting to become free from the ego must do so through selflessness – the opposite of egotism.”

Upbuild is essentially a consulting agency that brings Vedic knowledge and wisdom to leaders and teams of all kinds, especially those in the corporate world.

In my recent conversation with Rasanath Das below, we discuss the profound knowledge that stems from the Bhagavad Gita and other books that constitute the Vedas and how they relate to the COVID-19 pandemic, leadership, entrepreneurship, capitalism, finance, life in the 21st century, and the human condition as a whole.

Rasanath Das: What we do is essentially translate the principles of the Gita, in a language that is understandable to people who are leading teams, living in very complex situations, especially at this time, and putting it into practical action, breaking it down into steps.

So essentially, in plain Gita language, I would say, we help people develop the mode of goodness. That’s because once you get there, you see things more clearly; that’s the idea.

Ajani Charles: You seem to be the perfect person to have this conversation with, given what your organization does and given the fact that you live in Brooklyn.

You work with individuals that define Thrive Global’s target audience, and you see them every day on the streets of New York City.

Rasanath Das: Yeah.

Ajani Charles: So, capitalism is by nature competitive. And it implicitly involves striving, competition, capitalizing on the labor of others, and outsmarting others.

How do the Vedas approach capitalism? And based on the Vedas, how can we transcend our suffering while simultaneously living in a system that is by its very nature competitive and involves a lot of striving?

Rasanath Dasa: Great questions.

So the first thing to understand from the perspective of the Vedas is that any systems like capitalism, like democracy, are helpful systems, as long as the people working within those systems are working at a certain level of consciousness.

So, what the Vedas really give importance to is not just the system but the consciousness behind the system. That’s the first thing that we have to understand.

There have been a lot of books that have been written about the benefits of capitalism and the drawbacks of capitalism as well.

What I want to focus on is the collective consciousness around capitalism.

In my past, I worked within capitalism. I was an investment banker. And before that, I worked as a strategy consultant.

My understanding of capitalism is that it is the unlocking of potential, where you create an environment where every person can potentially thrive and live to their fullest.

Now what capitalism doesn’t say is that it has to be at the cost of somebody else.

What happens in the course of really building our own potential is that we feel that if somebody else is building their own potential, they are ahead of me.

Then I feel insecure about it. And it’s that insecurity that leads to unhealthy competition and exploitation.

So, it’s not capitalism per se, as a framework to unlock the individual’s potential and to help an individual thrive and live up to their full potential, but it’s the consciousness and the insecurity that creeps in when they see that a person within that system is doing “better” than they are doing.

So, there is often a zero sum game mentality within capitalism that is an unhealthy functioning of capitalism.

And that is that is where consciousness becomes a very important factor.

What the Vedas are talking about is that capitalism can function at a higher consciousness, or capitalism can function at a lower consciousness.

It’s not a fault necessarily with the system, but fault with the collective consciousness in which the system works.

Ajani Charles: That’s very interesting.

I was talking to someone about social media recently, and I told them that social media is like a knife; you can use a knife for cooking a healthy meal for yourself and your family or for cutting a birthday cake to celebrate your birthday, or you could use it to murder someone.

It depends on how you use the tool, and as you mentioned, it depends on the consciousness informing your use of the tool.

Also, I can’t believe you used to be a banker.

Rasanath Das: I’ve seen the system from the inside.

I was a banker between the years of 2006 and 2008.

The last recession was very historical from our point of view, and when you work within a system that is defined as a zero-sum game, then even people with good intentions give into their insecurities.

So, the challenge is how do we rise? How do we collectively rise in our level of consciousness within capitalism.

That’s where our focus is as an organization.

That’s what we want to do.

Ajani Charles: So, what do the Vedas, including the Bhagavad Gita, say about practical methods to raise one’s consciousness in the seemingly competitive environment that we live in?

Rasanath Das: So, the first thing that is required to raise consciousness is to understand the suffering that’s created, both for ourselves and for other people.

One of the challenges that we frequently encounter in our work is that it is almost this blocking of suffering, where there is an obstruction.

For example, somebody is working and making decisions; a manager is making certain decisions leading people who report to them to struggle and suffer.

And the management many times blocks the emotions out and says, “You know what, that’s their problem, that’s not my problem.”

And as soon as that happens, when we remove ourselves from really seeing what we are responsible for and owning that, that creates the first level of danger.

So, what the Gita first talks about is the following: if you are in a position of power or a position of decision-making, you are in a really responsible position. And that means you have to really care to look for the suffering you are potentially creating and take responsibility for that suffering.

That’s a very big part.

You could call it compassion, you could call it empathy.

There are many articles written about emotional intelligence, and one of the biggest components of emotional intelligence is being compassionate.

Ajani Charles: Right, that’s a big part of emotional intelligence.

Rasanath Das: The second part is really becoming aware of our egos, and our own egos’ insecurities.

When we are not aware, our insecurities essentially run our lives and decisions because they are actually working from our unconscious minds and pulling strings from behind.

The Gita strongly advocates that we become aware of our ego identities and the insecurities that they bring. And learn how to own those insecurities, be honest about them, and learn to work through them very systematically.

Otherwise, those insecurities will leak out to other people. And eventually, they will come back to bite us as well.

Ajani Charles: Right.

You gave the example of a manager not taking responsibility for the situation they created, which brings me to the next point I want to discuss with you.

In the society that we live in, we’re all interrelated, we’re interdependent to one another.

But, the way that capitalism and our society are often interpreted, we are usually independent. We’re disconnected and disjointed in many ways, even if we work in the same organization, even if we are on the same team.

So, what do you think of that idea? If our society does play out in that way quite often or sometimes, what are the implications of such a paradigm?

Rasanath Das: This reflects the binary way in which we think.

Earlier I had mentioned how within the framework of capitalism, everything often becomes a zero-sum game, meaning you either win or lose.

Ajani Charles: Right.

Rasanath Das: It’s the same thing with dependence and independence within capitalism. I think both of them exist.

And what is important is to actually create a very fine balance between the two.

So, going back to the question that you asked, there is independence.

We can make a choice.

We can make a choice whether we want to work for this manager or not.

But once we have chosen to work with a certain manager, the range of our choices decreases because we are dependent on the manager to empower us.

So, the manager has to recognize that there are people who are dependent on my position, because I have power.

I need to own that power in a way that helps everybody perform at their best.

Going back to the definition of capitalism, the basis of capitalism is helping people reach their full potential.

So, if we don’t create a safe environment, and if the people in power don’t feel responsible for creating a safe environment, then those people will not reach their full potential.

So, that is the responsibility that the manager has to accept. And that is also the dependence that people who report to the manager have to accept.

That cannot be ignored.

At the same time, people reporting to a certain manager do have the independence to bring the problems they see to the floor in a compassionate and gentle fashion.

So, I mean, there is a responsibility on the people who report to a manager to honestly bring issues that they are experiencing to the manager, and be very straightforward and honest. To be able to talk about that.

So, within capitalism, there is dependence, but there is also independence.

Ajani Charles: Right, ultimately there can be interdependence within capitalism.

A fine balance between dependence and independence.

Thank you for that.

Recently, I was hanging out with one of my oldest friends. I met him as a child.

He has been feeling a lot of insecurities lately because at the beginning of the pandemic he was let go from one of the largest media companies in Canada.

What do the Vedas say about addressing that level of insecurity?

We live in the most expensive city in Canada, all things considered.

At this point, you need to generate a decent income to live a minimalist lifestyle in Toronto, at least in some cases.

My friend has simple and complex material needs.

So, what do the Vedas say about his insecurities and about his anxieties about employment and generating an income?

Rasanath Das: So, it’s twofold. It’s a very complex question.

And the Vedas respond to that question, by elaborating on the layers of complexity that exist here.

And it’s essential to understand the complexity behind the question because the answer is not “okay, you push this button, and things will be fine.”

And I hate to reduce everything to that because that’s not so simple.

Sometimes we think that practicality means I can push a button, and I can get what I want.

But, the Vedas are practical because they help us understand the different layers of complexity, and they give efficient tips to deal with each layer of complexity in its own right.

And then they will also tell you what is beyond our control. To learn how to accept what is beyond our control.

First of all, I very deeply empathize with your friend’s situation because it’s a hard place to be. Not just financially but also emotionally.

The scars that being let go from a job are definitely difficult.

So, the first thing that is needed is to seek help from someone who can provide mental and emotional support.

That’s the first place that I would go to because we will need that support if we have to walk through this insecurity.

In the Gita, Arjuna is just about to fight. He’s in a situation like no other. It’s an existential crisis.

It’s excruciating, and Arjuna is a very competent man, extremely competent. But, at his most vulnerable place, the first thing he does is to seek support.

Knowing and recognizing that I cannot walk through this myself. That’s the first thing.

The second thing I would do then is to systematically break down my insecurities and tackle them one small step at a time.

So, for example, if the first level of insecurity is meeting my basic needs, then I would first focus on that and see how that can be accomplished.

That may mean that I have to take a temporary job or two.

It’s doing what is needed to get to a place of basic stability.

And many times, situations in our life put us in such places.

I was discussing this with someone today.

He’s the CEO of a company, and he was telling me that he has to have a conversation with one of his investors, and he told me how he has to swallow the pill of pride to have this conversation.

And I was telling him that’s true of a lot of people.

Historically, many people that have made a big impact in the world have all been in situations where they have to do what is needed.

So, there’s nothing shameful about it. It’s actually very courageous to be able to do that.

Once you reach that certain level of stability that will give you the opening, then think about, okay, how can I go from point A to point B, next.

So the first thing here is being surrounded by people who will give me mental and emotional support. That’s the first place.

The second place I would go is to think about the practical foundations of building systematic next steps [to build a career].

Ajani Charles: Thank you, that’s very profound.

My next questions relate to me specifically.

Before the start of the new year and over the winter holidays, I experienced extreme burnout. Quite possibly a life-threatening burnout.

And it’s ironic because I work with so many mental health organizations, and Thrive Global is a platform that was designed because Arianna Huffington, who founded the company, had a life-threatening burnout.

So, I was in the same position, earlier this year, despite knowing how to avoid such a position.

From my understanding of the Vedas and spirituality in general, I believe that I was trying to be my own Higher Power. I was attempting to be Krishna, as described in the Vedas.

I was trying to control the outcome of events. I was attempting to control myself, others, and my environment. And I was very rigid in my methods.

What do the Vedas say about that approach? And what are the implications of attempting to lord over oneself and one’s environment, whether it be in business or otherwise?

Rasanath Das: The basis of the Vedas, is the perspective that they offer on human life.

Human life is a journey of self-realization. That’s the goal. And that’s the premise for where the Vedas actually come.

So, the goal of human life, according to the Vedas, is not material success.

And while that doesn’t have to be ignored, that’s not what the Vedas are focused on.

Rather, what the Vedas are describing is if there is a certain amount of success that will give you the freedom to fully explore your journey towards self-realization, then that success is helpful.

So, given that perspective the Vedas are always reminding us of how the ego wants to be God.

The ego is not the real thing, it’s not the real identity, it’s not the soul, the spirit.

The soul is completely different from the ego.

And that is the journey of self-realization. Recognizing how we are not our egos, but the soul.

But, the ego always wants to control.

So what we’re experiencing when we say that we’re experiencing burnout, it’s actually a temporary collapse of the ego. It’s a temporary but unhealthy collapse.

At a certain point in time, the ego recognizes it can’t do everything. It recognizes that it’s limited, but it doesn’t like that. And then burnout happens.

It’s not happening intentionally, it’s happening really unintentionally, so that’s why it’s also very unhealthy.

So, what’s important here is to draw the lesson. The lesson is that the ego does recognize that “I’m not the controller.”

We recognize that the ego wants to control everything for its own sake. And then, that’s also what makes the ego insecure. And since the ego is insecure, it just decides to control by working more and more and more. It’s desperate.

Ajani Charles: Yes.

Rasanath Das: And when it’s desperate, it doesn’t recognize what it’s doing, it’s blind, until it finally collapses.

So, when we recognize what is happening in this system, or in this way of working, this dynamic, we also see how the best way to approach this is by acknowledging that I can’t control it. I can’t control the outcomes of everything that I’m doing.

The ego is afraid of what it will mean if I don’t attain my goals. And so it desperately tries to achieve at any cost. I want my goal to happen.

That is not hard work.

Hard work is intelligent; hard work is taking responsibility for my share of the work and recognizing that I don’t have control of the outcome. But I must do what is necessary to claim my role.

Ajani Charles: Right.

Rasanath Das: That’s a shift in consciousness. But to get there, it will take the help of someone who does it and who does it regularly.

Ajani Charles: So, 2021 is the first year since probably 2013 that I have not experienced frequent burnouts.

I’ve just started to slowly break this pattern of operating from the ego, at least in-part.

I also experienced burnout in the past, through spiritual practices.

I have engaged in spiritual by-pass for most of the last seven years, which is when you’re using spiritual practices and/or self-development practices in an egoic fashion to avoid true self-actualization, true introspection, true insight.

So, what do the Vedas say about that form of avoidance, and that form of maladaptive control? It’s very deceiving.

Rasanath Das: Very true.

In fact, right at the onset of the Gita, where the protagonist Arjuna has to fight this war that he doesn’t want to fight, Arjuna talks about how he just wants to live the life of a sage in the forest.

And the speaker of the Gita, Krishna calls him out and says that is avoidance. That is escapism.

So, as you rightly said, the ego can recruit anything for its own purposes.

And I have seen it in my own time; I was a monk for five years. And I saw how even in the monastery, many people wanted to become monks because regular life was hard. So, becoming a monk was a way to escape.

Ajani Charles: Wow.

Rasanath Das: And I have done that too.

Part of the reason why I became a monk was because I was very much bothered about death and dying.

And so, while there was a genuine spiritual seeking, there was a big part of my life where I wanted to avoid any more attachment to the world because I realized that attachment would lead to suffering.

And so, I’ve wanted to avoid any sort of putting myself in a situation where I would be attached.

And the lesson that I had to learn was you only learn detachment by learning to live in a situation where you can be attached and lonely.

So, I say all of that to say it’s imperative for us to look at the ego with a very fine-toothed comb, whether we are engaged in spirituality or whether we are going about our jobs because the ego is a very tricky thing.

Ajani Charles: Yes.

It’s unbelievable how I can deceive myself, and how my intellect is quite often an obstacle to transcending these patterns that cause me to suffer.

Rasanath Das: And that’s the intellect that’s fuelled more by the ego and less by the spirit.

Ajani Charles: Right.

Rasanath Dasa: So, it depends on where the intellect is plugged into.

Is it plugged into the ego, or plugged into the spirit?

That’s spiritual work. The spiritual work is re-plugging the intellect into the spirit.

Ajani Charles: Right.

I have one last question since we have about a minute here.

Many people in our day-to-day lives and the media are talking about when the pandemic ends; they’re attempting to predict the future.

And from my perspective, they may be causing themselves to suffer if they have a specific end date in mind and if that specific end date doesn’t come to fruition.

So, what would you say to individuals, whether they’re professionals in an organization, entrepreneurs, leaders that may be suffering from the moving goalposts of the pandemic coming to an end?

Rasanath Das: It’s an excellent question.

I feel the same way. I want the pandemic to end. Both for myself and many others, so the expectation that the pandemic will end at a certain point is natural because that gives hope. And we always have to be hopeful.

I think where it becomes a tricky situation is when that becomes an expectation. And that expectation becomes an obsession.

So, what’s important here is to keep the hope of life and remember that the pandemic will end.

We think it will end by September or October. And so, be hopeful about it. And at the same time, recognize that it may not end by September or October. It may not.

And so, what do I do about that?

And then that brings us to the present.

What do I need to do now in order to position myself so that I am prepared for what the next journey is?

So, the idea is to use this time wisely, grow ourselves, and really understand ourselves because the pandemic, as difficult as this is, provides an opportunity, a unique opportunity, for personal growth.

And I use the word personal growth very deliberately because it’s usually an exhilarating emotion when we talk about personal growth.

But my own personal work and the work that we do has taught us that when somebody is really growing, they feel like, “my God, this is the most terrible place I’ve been.”

Ajani Charles: Yes.

Rasanath Das: So, the pandemic is something like that.

It’s a situation where we are being stretched and we don’t have a say in it.

Ajani Charles: Like Arjuna.

Rasanath Das: Exactly right.

And that’s a very unique position to be in, when we ask ourselves “what lessons do I need to learn at this time?”

Learning how to surrender. How to let go. How to not expect. How to understand my insecurities. Those are treasured places to go to.

And while it may be uncomfortable, I can say that when we do go to those places, and when the pandemic is over, we will be in a place to provide, give to the world, and impact the world from a very different perspective place.

That’s what this time is about. It’s preparing us for something much bigger.

Ajani Charles: Thank you so much, I feel like I could ask you questions for at least four more hours, but you clearly have a family to attend to.

Rasanath Dasa: Thank you so much.

Let’s stay in touch.